Back in 2010, I Googled my parents’ names, just to see if any information about them was out on the internet. They were aging, and I wanted to ensure their safety, both online and off.

I was also curious. Neither of them had ever owned or operated a computer. Heck, even operating a cell phone was a stretch, and I’m not sure either of them ever used the one they bought for emergencies, despite my repeated and patient instructions. Would anything be on the internet about people who had never been on the internet themselves?

I was surprised to find my father’s name (Howard Pramann) associated with a blog called, “My Musical Family” by Joy Riggs, a writer based in Northfield, Minn. The post was titled, “Music: The Anti-Drug.” It featured an interview with my father about his experience playing the cornet under the instruction of Joy’s great-grandfather, G. Oliver Riggs (the G stands for George, a name Mr. Riggs did not like so did not use). Mr. Riggs was adamantly against smoking, especially since his musicians needed good lungs to play. His anti-smoking lectures no doubt kept many a young man from taking up the habit.

After reading the post, I vaguely recalled my parents recently mentioning something about my dad being interviewed, but I didn’t understand that it was for a blog.

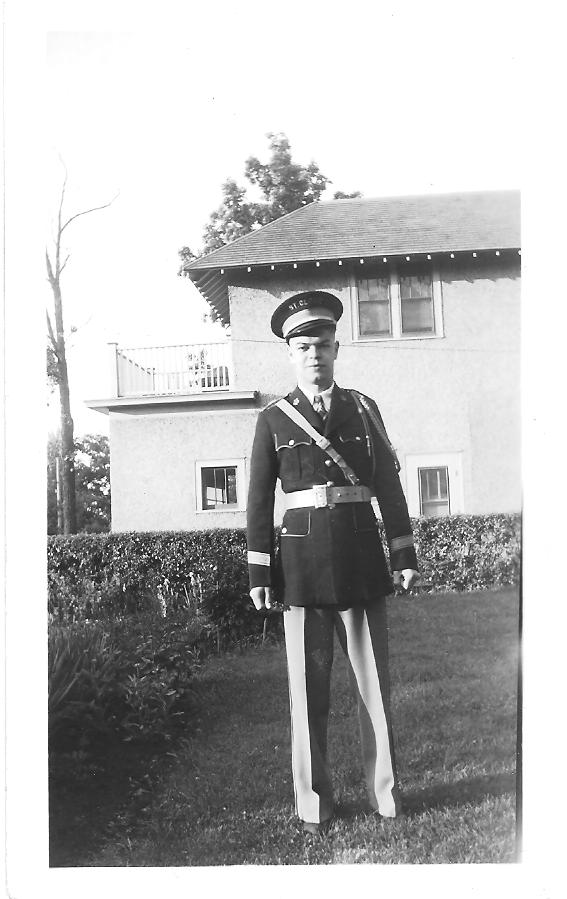

My father, Howard Pramann, in his spiffy band outfit in St. Cloud in 1937.

I shared the post with my family members and parents, and wrote a thank-you e-mail to the author. She responded quickly, and we corresponded a few more times. She explained she was writing a book about G. Oliver Riggs, who was an influential and prolific “Minnesota Music Man.” He developed and directed bands in communities like St. Cloud and Crookston, Minn., and even in Montana. My father, Howard, played in the St. Cloud band for eight years, from age 10 until he graduated high school.

Late this summer, I received a message from Joy through my author website. She noticed I was a presenter at the North Shore Readers and Writers Festival in Grand Marais, which she planned to attend. She was looking forward to meeting there, plus she had published the book about her great-grandfather.

After receiving her message, I looked at Joy’s author page to see how I could lay hands on a copy of her book. I noticed she was doing a signing at a local bookstore a few weeks before the festival. I told her I would see her at her signing and later at the festival.

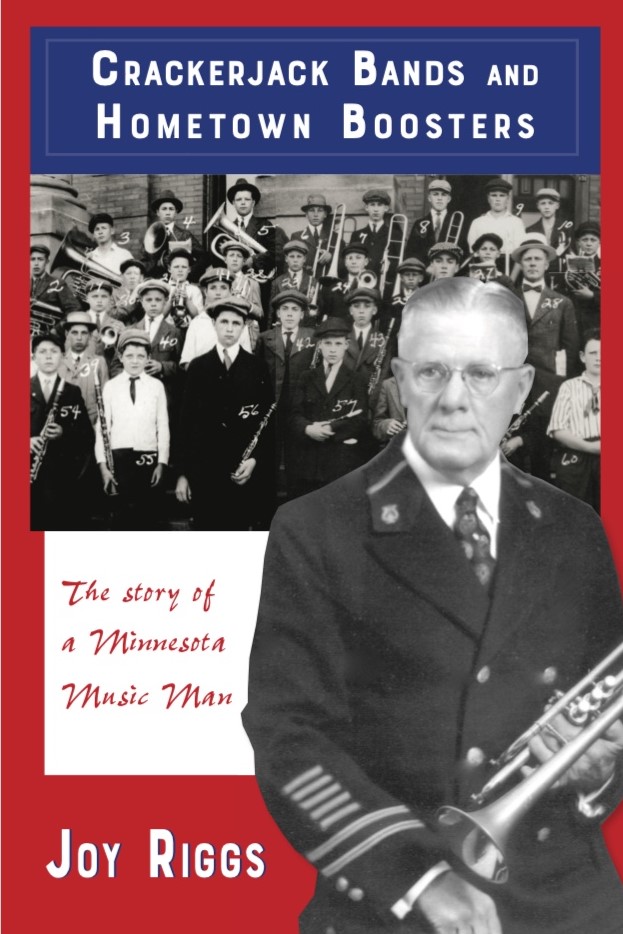

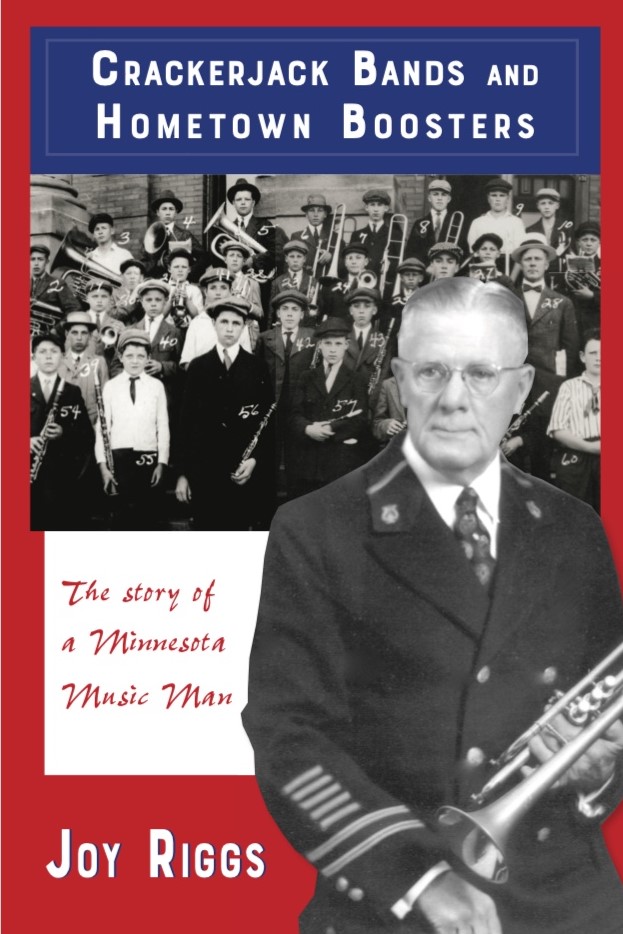

We met at the bookstore and had a nice chat. Not long after, I read her book, entitled “Crackerjack Bands and Hometown Boosters: The story of a Minnesota Music Man.” (Noodin Press, 2019.)

We met at the bookstore and had a nice chat. Not long after, I read her book, entitled “Crackerjack Bands and Hometown Boosters: The story of a Minnesota Music Man.” (Noodin Press, 2019.)

What immediately impressed me is how Joy interweaves her personal story with information about her great-grandfather’s life. This made the book much more interesting, as readers are able to experience the thrill of discovery that Joy found during her research process. Readers also learn that this book was her return to journalism after many years of subsuming her career to her growing family’s needs.

Her vivid prose won me over to the importance of her topic – bringing to life a bygone era, when public bands were the best form of entertainment in town and brought communities together. Although G. Oliver was a stern taskmaster, Joy’s book shows how his methods and discipline influenced his young pupils in a positive way throughout their lives.

Since my father was one of those pupils, it was thrilling for me to see photos of the venues where he might have played, and learn about the people he performed alongside. I was particularly interested in seeing pictures of my father’s piano teacher, who was G. Oliver’s wife, Islea.

Reading Joy’s book made me wish my father (who died in 2016) had spoken more about his community band experiences. When I complained about having to practice the required half-hour per day on my French horn in junior high and high school, he could have retorted with things like, “When I was your age, we had to practice four hours per day. What are you complaining about?”

I would have liked to hear him describe the contests his band won, and the parades they marched in. But through Joy’s book, I was able to follow the band’s triumphs and challenges across the years.

Joy describes her interview with my father in Chapter 13. He’s mentioned again on page 228 as playing a cornet duet before an audience of 5,000 people in a theater in St. Cloud.

To my surprise, Joy even refers to me on page 200, although not by name, when she discusses our initial correspondence.

Of course, I’m going to like any book that has me in it (ha, ha). But even if I wasn’t included, I’d still recommend Joy’s book for anyone who is interested in Minnesota’s musical history and the important role the arts can play in people’s lives. I gave it five out of five stars on Goodreads.

We met at the bookstore and had a nice chat. Not long after, I read her book, entitled “Crackerjack Bands and Hometown Boosters: The story of a Minnesota Music Man.” (Noodin Press, 2019.)

We met at the bookstore and had a nice chat. Not long after, I read her book, entitled “Crackerjack Bands and Hometown Boosters: The story of a Minnesota Music Man.” (Noodin Press, 2019.)

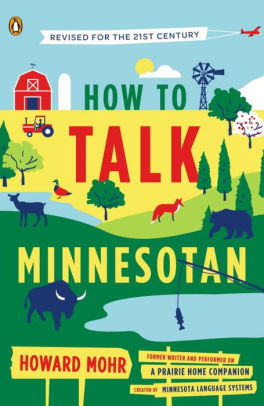

The first version of this book, published in 1987 and later made into a video, helped me understand my own culture. Before reading it, I never understood that the “long good-bye” was something unique to my state of Minnesota. (The long good-bye is where it takes at least three tries to leave a friend’s home before they will actually let you go.)

The first version of this book, published in 1987 and later made into a video, helped me understand my own culture. Before reading it, I never understood that the “long good-bye” was something unique to my state of Minnesota. (The long good-bye is where it takes at least three tries to leave a friend’s home before they will actually let you go.)

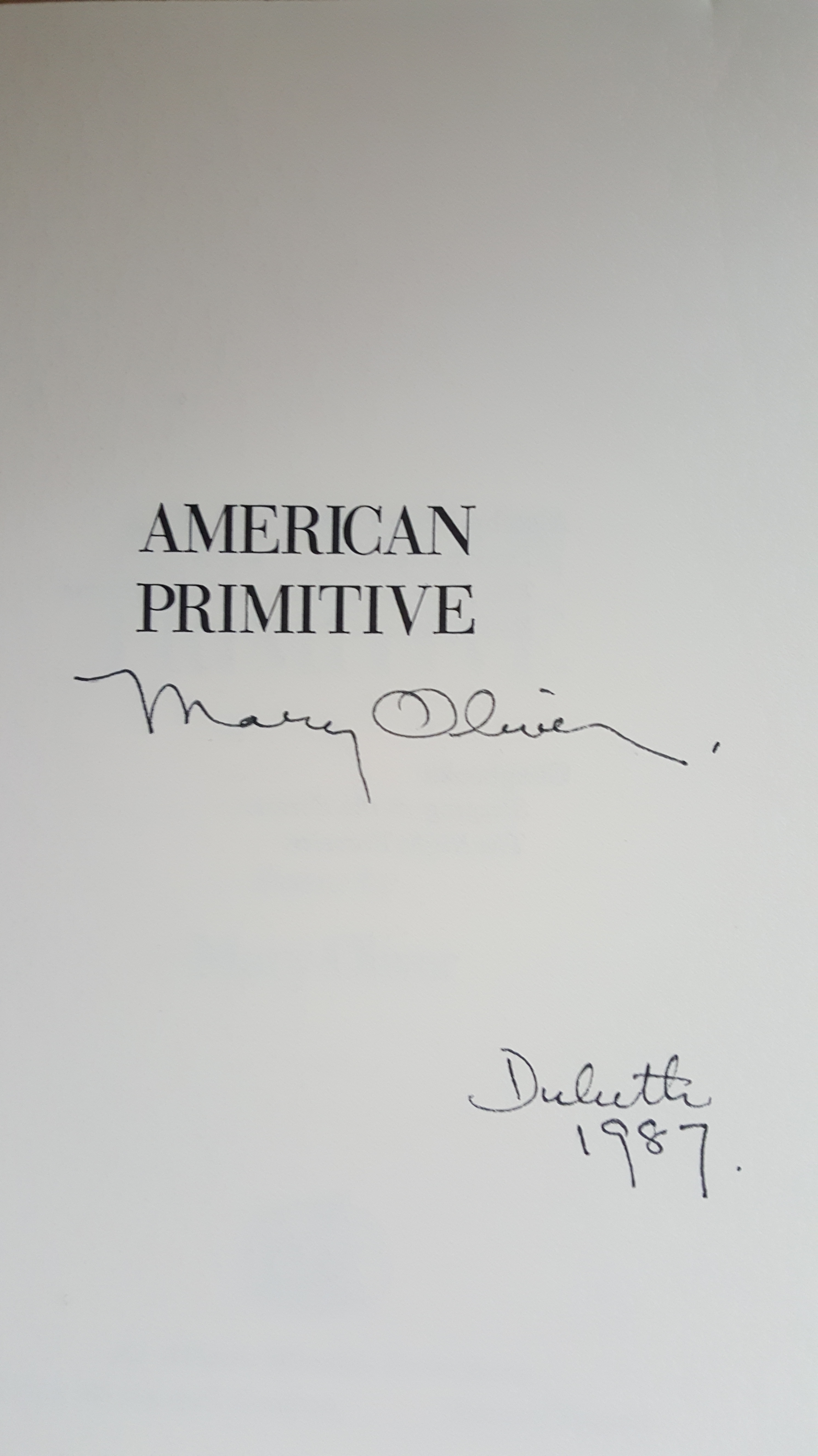

I’ve long been a fan of her work. I even was able to see her read in person in the hinterlands that are Duluth way back in 1987. Her autograph is on my copy of “American Primitive” as proof!

I’ve long been a fan of her work. I even was able to see her read in person in the hinterlands that are Duluth way back in 1987. Her autograph is on my copy of “American Primitive” as proof!

Greetings! I had the privilege of being interviewed last week on the local Wisconsin Public Radio affiliate, along with Julie Gard, a poetry professor at the University of Wisconsin-Superior, and Julie Buckles, the public relations person for Northland College in Ashland, Wis.

Greetings! I had the privilege of being interviewed last week on the local Wisconsin Public Radio affiliate, along with Julie Gard, a poetry professor at the University of Wisconsin-Superior, and Julie Buckles, the public relations person for Northland College in Ashland, Wis.