Once upon a time, a woman lived alone in the northern Minnesota wilderness. Except, she wasn’t really alone. Birds and otters kept her company. Canoeists stopped by her island on Knife Lake near the Canadian Border. At one time, she even ran a resort there.

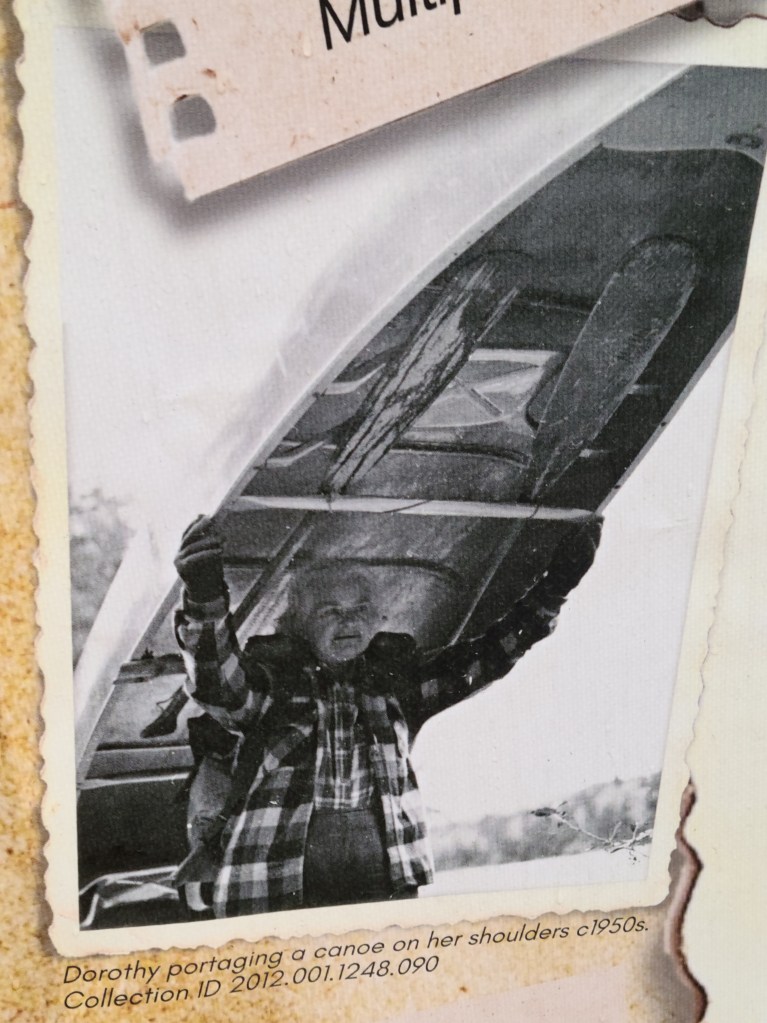

But after the land was designated as an official roadless area and then a Wilderness with a capital W, making a living became more difficult for the woman, not to mention getting supplies. Rogue sea plane pilots tried to help her, but they were arrested. The only thing the woman could do was haul in the supplies she needed by canoe, portaging five times over the 33 miles to civilization.

In 1952, a writer with the Saturday Evening Post visited her and wrote a story about “The Loneliest Woman in America.” The article turned her into a national legend – a woman living alone among wolves and braving minus 50-degree winter temperatures. But the woman always contended the writer got it wrong, she was never lonely, even in winter.

One day, she was cleaning and found dozens and dozens of glass bottles left from when her resort served pop (as we call it in Minnesota). Rather than haul out the bottles and discard them, Dorothy Molter (as was her name) got the idea to make root beer for passing canoeists in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.

She hit the jackpot. If there’s one thing most wilderness campers appreciate, it’s a fizzy cold drink after days away from civilization. Dorothy made her drinks with root beer extract, sugar, yeast, and water from Knife Lake. They were cooled on ice cut from the lake in winter. Canoeists donated a dollar per bottle.

Dorothy made root beer for years. At the height of her business, she produced 12,000 bottles and still couldn’t keep up with demand. She was trained as a nurse and aided any canoeists who needed help by sewing up cuts and removing fishhooks from various body parts. She once saved the lives of a father and son who got hit by lightning in a sudden summer storm. Dorothy also nursed wild animals, including a crow and a mink.

A strong and plain-spoken woman, Dorothy didn’t swear or curse, but she didn’t mince words either. Her philosophy for surviving in the wilderness could be summed up in the sign she posted at her home on the Isle of Pines. “Kwitchurbeliakin,” it advised.

Dorothy continued living in the wilderness until she was in her late 70s. She kept in touch by radio, checking in with Forest Service staff daily. One winter day she didn’t check in. Then another day passed with no contact. A wilderness ranger made the trek and found her dead of a heart attack from hauling wood.

Although Dorothy’s time passed, her memory is preserved in a museum named after her in Ely, Minnesota. The fame and good will she garnered through her lifestyle prompted its formation.

Russ and I had heard of Dorothy over the years but never had a chance to meet her or visit her museum. We thought we were out of luck on a recent camping trip to Ely because a brochure we happened upon said the museum was closed after Labor Day.

With drizzly weather forecast, Russ and I ditched hiking plans and meandered into Ely to see what struck our fancy. We had driven though the whole town with no fancies struck, when we passed the sign for the Dorothy Molter Museum on the outskirts. The sign read “Open.” So, we turned in, hoping the sign wasn’t just the product of end-of-season-forgetfulness on somebody’s part.

The museum really was open! We spent a couple of hours touring Dorothy’s cabins, which volunteers had hauled out of the wilderness to house her artifacts. We enjoyed watching excerpts from a video about Dorothy’s life. We viewed her root beer-making equipment and perused the gift shop, where visitors can buy a bottle of Dorothy’s root beer. Despite the drizzle, we also got a bit of hiking in on the quarter-mile trail in the pine plantation surrounding the museum.

We left glad to see Dorothy’s memory preserved. As one of the museum signs says, “Although Dorothy has been gone from Knife Lake for over 30 years, we hope that you find inspiration to live your lives like she did, in harmony with the environment, with integrity, helping humankind, and making a contribution toward a better world.”