Last winter, a rabbit lived in our backyard, sheltering under our neighbor’s shed. We’d awaken in the morning, shuffle downstairs and take a look out our window on the landing where we could see the back yard. More often than not, there she crouched, a brown cottontail, nibbling what grass wasn’t already covered by snow.

Since both of our dogs died, we’ve been petless. We saw this rabbit so much, it just seemed natural to start becoming a little attached. I began leaving her offerings of dried orchard grass, remnants of our deceased guinea pig. I also initiated a naming contest for the bunny on Facebook. My friend June won with the moniker of “Tater Tot.” It fit – the shape and coloring were approximately right.

Tator Tot survived the winter and this spring we noticed several Tiny Tots scampering around the backyard – her children, no doubt. They didn’t seem to be doing any damage to my hostas, just hiding under them instead of eating them, so we welcomed these new additions to the yard.

I suspect that Tator Tot eventually left our yard for the forest at the end of our road. We sometimes saw a rabbit fitting her description during our woods walks. Her Tiny Tots hung around for several weeks and then seemed to disappear. I hope they, too, found their way to the forest. But they could have easily been eaten by a neighborhood cat or a fox.

I rather miss these foster pets. They were easy to take care of. No fuss, no muss.

I recently read Linda LeGarde Grover’s book “Gichigami Hearts.” LeGarde is a former neighbor of mine; we grew up in on the same street on the other side of Duluth. Her book offers a Native American perspective of our old neighborhood. In one chapter, “Rabbits Watching Over Onigamiising,” she describes how seeing rabbits reminds her of the Native spiritual being, Nanaboozhoo. Now, if you’ve read my book, “Eye of the Wolf,” you know that Nanaboozhoo is a trickster – part rabbit, part human. He embodies the best and the worst of humans and the supernatural.

LeGarde’s backyard bunnies savored her tulips, necessitating a change the next spring to planting marigolds, which she says the “rabbits nibbled on, but not much.” LeGarde writes that planting different flowers rather than trying to eradicate the bunnies was a good compromise. “We are all here to live our lives . . . We know from traditional teachings that all animals are important to the earth, that no animal is ranked higher or lower than any other in the eyes of the Creator, and that all have a contribution to make.”

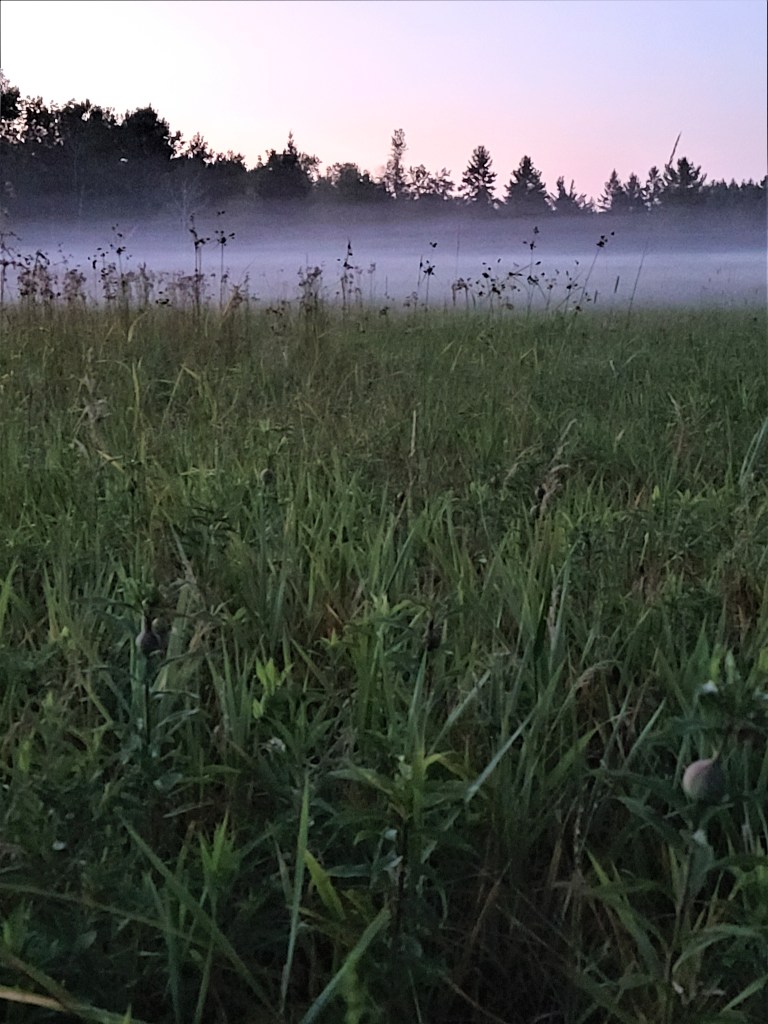

She recounted a conversation she had with a friend about seeing rabbits on clear nights in the moonlight in winter, sitting with their legs folded under them like a cat – like they were waiting for something. LeGarde’s friend told her, “When we see them like that at night it is because the rabbits are watching over us, over a sleeping world and our dreams.”

Here in the north, we have two kinds of rabbits: cottontails like Tator Tot and snowshoe hares, which are larger and turn white in winter. Rabbits in the moonlight reminded me of one of my favorite chapters in northland author Sigurd Olson’s book, “The Singing Wilderness,” about the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. It’s the chapter called “Moon Madness,” where he recounts seeing hares on his moonlight walks.

“If, when the moon is bright, you station yourself near a good rabbit swamp and stay quiet, you may see it, but you will need patience and endurance, for the night must be cold and still. Soon they begin to emerge, ghostly shadows with no spot of color except the black of their eyes. Down the converging trails they come, running and chasing one another up and down the runways, cavorting crazily in the light.”

Olson concluded that moonlight “made animals and men forget for a little while the seriousness of living; that there were moments when life could be good and play the natural outlet for energy.”

It’s comforting to think of rabbits or hares cavorting crazily in the darkness or quietly keeping watch. I never saw Tator Tot or the Tiny Tots at night because I was, well, sleeping. Perhaps I never saw them because the magic they worked was so effective.

When I emerged from my office building in Superior yesterday evening, I was thinking about all this. As I walked, who scampered across the parking lot pavement not ten feet from me? A big fluffy cottontail. She looked suspiciously like Tator Tot.