Russ and I sacrificed a 40-day winning streak on the NY Times Connections word game to head to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness where there is no phone or internet service. We traveled with our friends Sharon and Mike to Brule Lake – a place I last visited 35 years ago.

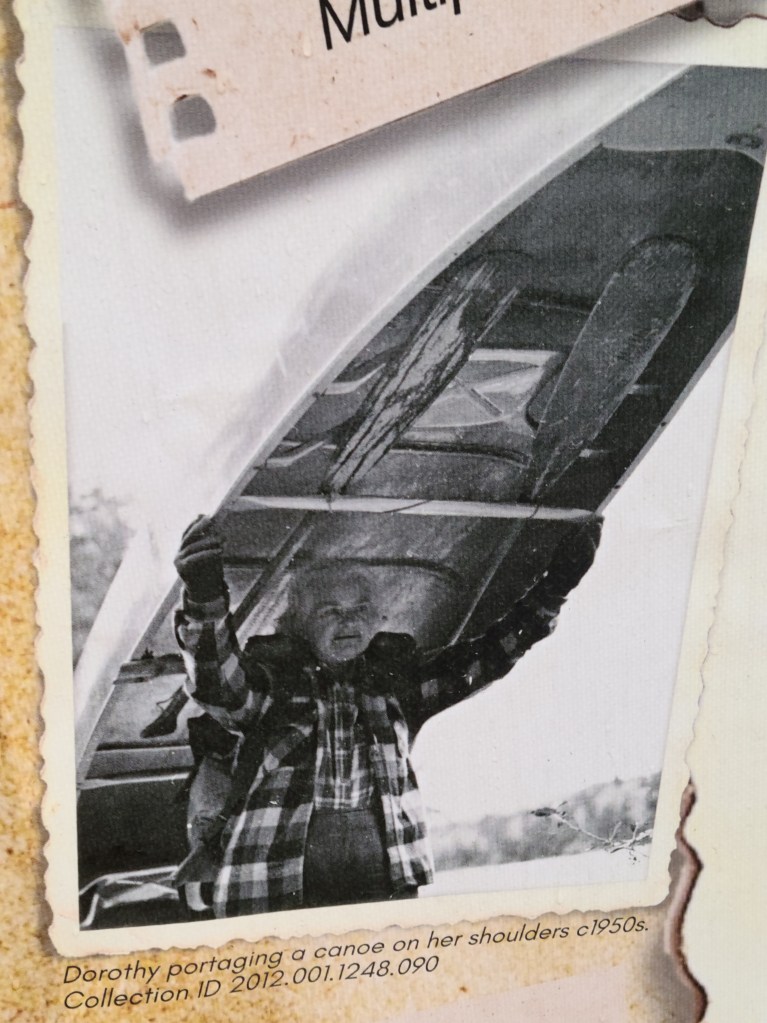

To go easy on our aging bodies, we decided to do a canoe trip without any portages. (Portages are where you carry your canoe overturned atop your shoulders on a rugged trail to the next lake.) Brule Lake is large enough to spend several days there without needing to go anywhere else.

We were partially successful in meeting our goal. The only “failure” came on our third day of tent camping when Sharon and Mike decided to portage to a small lake for better fishing. We hiked the portage without our canoe to see if the lake was worth the effort of hauling it there. With forested hills and a cute island, the beauty of the new lake and the short length of the portage convinced us to bend our no-portage rule. It was a true wilderness lake with no campsites or other signs of human habitation.

To share the pain of portaging, we opted for a two-person carry, where we carried the canoe over the portage with one of us on each end of the watercraft – no hefting it up onto one person’s shoulders.

We were glad we did; canoeing on the lake offered views of a loon and its baby. We found the loon’s nest on the small island, where we ended up eating lunch much to the delight of the ants there. Our presence was probably the most exciting thing to happen to them in years! Sharon and Mike caught enough fish to feed us all dinner that night.

After we spent several hours on the lake (which I am purposefully not naming because Minnesotans don’t do that with good fishing lakes), the sky began to darken. We decided to head back to our campsite on Brule Lake. We couldn’t relay this to Sharon and Mike because they were at the far end of the lake.

We made it across the portage and out into the bay when the storm broke. The first drops of rain were huge and cold. We were wearing our swimsuits because we expected rain, so we didn’t mind being wet. What we did mind was the wind and the thunder/lightning! Yelling through the gale, we briefly considered riding out the storm on land, but we were so close to our campsite and the lightning was far away enough that we decided to power through and hope we didn’t get struck. (That was reckless of us, I don’t recommend staying on the water in a thunderstorm. Don’t try this at home!)

We made it to camp and I quickly climbed into the tent to get into dry clothes. Russ was already so wet, he stayed outside. Once I changed clothes, the wind picked up even more. Russ had to tie down our lightweight Kevlar canoe to keep it from blowing away. From inside the tent, I held down the side the wind was hitting so that the stakes wouldn’t pull out of the ground. After what seemed like hours, the storm abated.

We were a little worried about Sharon and Mike, but this wasn’t their first BWCA Wilderness trip, so we assumed they’d be okay. But as the hours ticked by and the sun lowered, we began to discuss how long to wait until beginning a search for them. Not long afterwards, we heard them paddling back to our campsite. We greeted them with shouts of “You’re alive!”

They explained that they also stayed on the water during the storm, riding it out next to shore. (That was reckless of them, I don’t recommend staying on the water in a thunderstorm. Don’t try this at home!) Then they stayed on the unnamed lake to fish more. We ate the fruits of their efforts with relish that night – the first non-freeze-dried dinner Russ and I had eaten in days.

The next morning, our final morning, another thunderstorm rolled through, but it wasn’t as strong as the previous one. Once it stopped, we packed up our soggy gear and headed to the canoe landing, wanting to cross Brule Lake as quickly as possible in case another storm was gathering. Sharon and Mike planned to leave later.

We made it back to the landing. Driving home, we appreciated the gradual return to civilization. Backwoods gravel roads gave way to pavement that led us past homes and eventually to the small town of Lutsen. The day turned hot and muggy, so we stopped for ice cream on the way home to Duluth.

Now we’re back winning Connections again: 6 games so far. But we both agree this wilderness trip and the memories of spending time with good friends, listening to loons yodel, telling stories around the fire, and surviving thunderstorms were more than worth breaking our streak.