This story was originally published in “Minnesota Flyer” magazine as a two-part series in October and November, 2024. Offered here with permission. See part 1 here.

The Rescue

How could something like this happen to a plane piloted by someone as safety conscious as David Potter? What a waste of young, healthy men! All because of darkness, a cold front, and perhaps an interrupted sleep schedule.

Vermont Historian Brian Lindner thinks fatigue due to their training schedule is “entirely possible. Some or all of the crew could have been sleeping. Jimmy Wilson certainly was.” He also thinks it’s possible that one or more of the pilots fell asleep. “Think about it. You’ve got the drone of the engines, it’s total darkness, there’s nothing to see out the window. But we’ll never know.”

My Uncle David died that day. When the plane hit the mountain, the fuselage was catapulted into the air, falling to the ground and skidding several yards to a stop at the bottom of a steep embankment. Inside, Wilson was unconscious. Thanks to his position farther back in the plane and perhaps to his nest of parachutes, Wilson’s only injuries were a gash over his right eye and a broken right knee. He was the only survivor.

The blow to Wilson’s head rendered him semi-conscious for two days and left him unable to protect himself from the cold. As he lay in the shattered fuselage, temperatures hovered in the low twenties as the cold front continued to move in. The skies clouded and snow began to fall.

Initially, there was little concern when the plane didn’t return to Westover Field. It was authorized to land at any major airport along its route if it experienced difficulties. However, come dawn, all military bases and Civil Air Patrol units in northern New England and New York were notified that the bomber was missing.

Civil Air Patrol (CAP) units flew throughout the day but found nothing. Same thing the next day. Two days after the crash, the clouds finally lifted, and they spotted the wreckage 80 feet below the southeast corner of Camel’s Hump summit.

Map coordinates were issued shortly after the sighting, but it was soon discovered they did not match the original description and placed the plane on the wrong side of the mountain. Volunteer CAP wing Commander, Major William Mason made a hurried call to Westover Field to report his discovery of the error. A captain there bluntly told Mason that the Army knew what it was doing and that the CAP should consider itself off the case.

The Army searchers were all gathered on the wrong side of the mountain! Undeterred and desperate, Mason, who needed to tend to his factory, called his son, Peter, a high school senior and CAP cadet, asking him to gather several other cadets and organize a rescue attempt of their own.

Peter quickly assembled seven cadets, ranging from seventh to twelfth grade. Meanwhile, Mason searched for someone who could transport and guide the cadets up the mountain. Eventually, a local dentist and outdoorsman, Edwin Steele, was found. Slogging through six inches of new snow, he guided the cadets up the slopes.

As the sun began to set, the group neared the summit. They soon spotted two parachutes flapping in small trees near the base of the cliff below the summit. Crushed trees and wreckage were strewn everywhere; the smell of aviation fuel filled the cold air. The cadets struggled through the new snow and thick underbrush to pick their way through the crash site.

In the distance, they heard a faint call. They scrambled through brush down a steep embankment where they discovered Wilson sitting outside, propped up against the remains of the fuselage. In his hypothermic state, he had partially removed his heavy flight pants, opened his jacket, and taken off his gloves and boots.

The resourceful cadets wrapped Wilson in parachutes. To protect him from the wind, they made a lean-to from heavy canvas engine covers they found inside the wreckage, and saplings. They started a fire with the aid of an oxygen bottle from the plane. By this time, it was dark, and they were certain no one else had survived the crash. Between them, the rescuers only had one sandwich, and this they fed to Wilson.

The group spent the night on the mountain using the parachutes and engine covers for protection. One cadet bear-hugged Wilson to warm him. According to Lindner, “This act clearly saved the young airman’s life.”

At first light, Steele and two cadets hiked back down the mountain–they’d need more help to transport Wilson. As they neared the base of the trail, they met some of the Army rescuers who were on the right path, at last. The Army men headed up the mountain and once they reached Wilson, placed additional wrappings around him and dressed his wounds.

As the cadets, Army men, and civilian guides carried Wilson down the difficult trail, the remaining men gathered the fragmented remains of the dead, including David, and carried them down the mountain.

Aftermath

Wilson was loaded into an Army ambulance approximately 63 hours after the crash on a Wednesday afternoon. That evening, telegrams were sent to the families of the dead crewmen with the sad news. Although Wilson’s injuries were comparatively minor, he received severe frostbite, which required amputation of both his hands and feet. He was the first of two soldiers in World War II to undergo such a radical surgery.

Despite challenges and hooks for hands, Wilson later completed his education and became a successful attorney in Denver. Wilson visited David’s parents several times in Springfield and also dedicated a new flagpole at a Memorial Day ceremony at the city cemetery.

The cadets were instructed not to talk about the crash. As a result, rumors abounded in Waterbury and the rest of Vermont. Some thought it was a Nazi spy plane that had crashed. Others thought it was a cargo plane. Likewise, the crewmen’s families never got the whole story, only four telegrams informing them the plane was missing, then that it had been found, that their loved one was dead, and lastly, that his body was coming home.

Thanks to Lindner’s diligent research, we know more now. To read a story about how he became interested in the crash and for more information about the crew members, visit the Vermont Digger website.

My family visited Camel’s Hump in 1970 when I was six. We stayed in Waterbury with Dr. Steele and his wife. While I stayed at the Steeles’ watching television and eating M&Ms (which seemed like the ultimate in happy decadence for me at the time) the rest of my family hiked up the mountain guided by Steele.

I recall Steele as white-haired, old (but to a child everyone is old!) and kind. His wife was also very kind to me.

While she was on the mountain, my mother collected a few small parts of the plane. Back at home in Duluth, she strung them from pieces of wood to make a rather macabre mobile. It hung in my father’s ham radio room. Part of me could understand why she did it to honor David. As I aged, part of me began to think of it as a gruesome reminder.

My mother and brothers returned to Waterbury in 2004 for a sixtieth anniversary commemoration event of the crash organized by Lindner. I had young children at home at the time and couldn’t travel. At a local church, more than a hundred relatives, friends, and interested citizens attended a dinner and evening presentation about the crash.

Three former CAP cadets (now in their seventies) were feted along with Wilson’s widow and their two adult children, a daughter of Ramasocky the copilot, and my family. Afterward, Lindner hiked up Camel’s Hump with my brother Dave.

Over the years, souvenir-hunters like my mother have taken pieces of the plane and its engines off the mountain. A college student extracted the star insignia from the plane and hung it in his dorm room, only to leave it behind when he moved on. The most visible reminders left of the plane now are the wings, which lie overgrown by trees and brush.

Uncle Dick

Dick worked on his father’s stockyards, specializing in feeding livestock for market. He left the farm in 1942 to work as a copilot with Northwest Airlines (which is now Delta Airlines), and later with the Chicago and Southern airlines out of New Orleans. He married Cleo Abbet, a Springfield woman, in 1943.

In fall of 1944 when David was at Westover Field, Dick appealed to take leave from his commercial piloting to enlist in the Naval Air Corps. His eyes were better than David’s, so he was able to enter the military more easily. Eventually, he trained at Corpus Christi, Texas.

While researching this story, I noticed that David’s crash was on Dick’s birthday. I imagine that must have put a terrible damper on his celebrations for years. But perhaps it made him realize how precious life is and become more thankful. I don’t recall my family ever discussing this connection.

A few months after David’s crash, Dick was transferred to Alameda, California, and became a pilot in the naval air transport service in the Pacific. Cleo followed him to California and lived in Oakland. True to his goal to fly big planes, Dick ended up flying Douglas C-54 Skymasters for the Navy over the Pacific on noncombat missions like air-sea rescues. After the war, he returned to commercial piloting, eventually flying 747s when they were put into service in the 1970s.

Historian Lindner spent several days with Dick and Cleo in Springfield where he met family members and pursued more research on the crash. During that time, Dick mentioned that he only had one major incident while flying and this was when an engine died on his 747 on takeoff.

During Dick’s recounting of the incident, Lindner recalls thinking, “Dick was talking about his flying emergency and he just seemed so cool, calm, and collected. He’s telling me about it like it was next to nothing. So, quite frankly, I think he and David were very much alike.”

My cousin Ginger Beske, who met Dick more often than I did said he eventually soured on large planes and switched to smaller planes. “He didn’t want to be responsible for so many lives,” she said. Perhaps it was after this incident with the 747?

Dick flew for Delta Airlines for years out of Atlanta, Georgia. When he retired, he was one of their top pilots in terms of seniority. He died at the ripe age of 86, still married to Cleo and with several adopted children who gave him grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

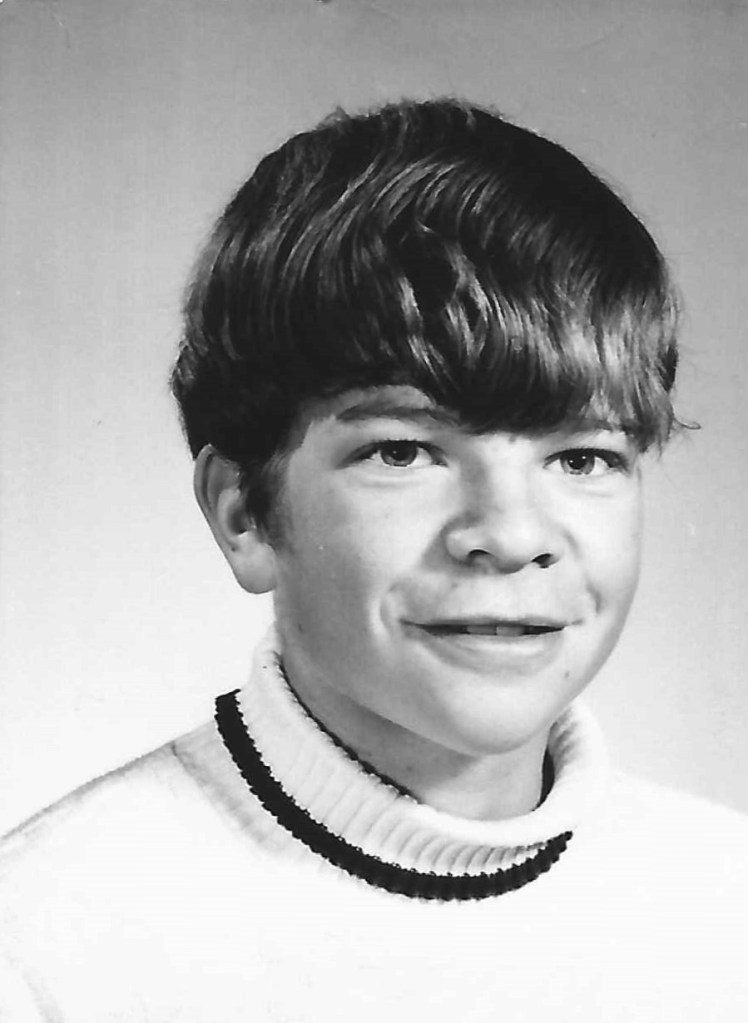

Brother Dave Pramann

Although Dave’s swimming teacher said he was a natural, he never took to water like I did. He was drawn instead to the rush and freedom of air. What could draw someone into aviation when it killed his namesake?

Dave remembers Uncle Dick flying a charter plane into the airport in our hometown of Duluth, Minnesota, once when Dave was very young. “He let us up into the cockpit. Then when he left, he stuck his head out the window and waved goodbye. I thought that was the coolest thing ever.”

Dave estimates he might have been three years old. Afterward, whenever anyone asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up, he said, “A pilot. I knew I was destined to be a pilot, and that was from Uncle Dick and David.”

When I asked him if he always knew he was named after Uncle David, my brother said, “You know, Mom never actually came out and said I was named after her brother, but I figured it out pretty quick.”

When he was thirteen, our parents gave Dave his first flight as a birthday present. Dave said the 30-knot winds made it, “the bumpiest airplane ride I’ve ever been on!” His motion sickness was severe enough to last through the next day.

As an adult, Dave criticized the Cessna pilot for not paying more attention to him and his green pallor or being prepared for a passenger’s airsickness. “But he was probably a young guy looking to build hours,” Dave conceded.

The rocky flight didn’t deter him. “I was like, ‘I’m gonna learn to fly.’ Even some of the best pilots in the world like Chuck Yeager, who was the first guy to break the sound barrier in the world, got sick his first time in an airplane. Eventually, I got used to it and it’s not a factor for me anymore.”

Like his Uncle David before him, my brother also lacked perfect vision. The U.S. Air Force had raised its standards again and weren’t taking pilots with glasses. So, he decided to major in meteorology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. That’s where he met his wife Mary. They ended up in Denver, where Dave worked 10-hour days making about $18,000 a year for a weather consulting company. He enjoyed it but also pursued his commercial instrument flight rating, thinking he’d try to get hired into commercial aviation, which didn’t have the strict vision standards. He was building up flight hours when air traffic controllers decided to strike in the 1980s.

“I knew the business because I was a pilot,” Dave said. “I flew out of tower-controlled airports regularly, so I knew what their job was. Plus, I saw an interview on Denver television about a couple of controllers. Each made $60,000 a year. I was like, ‘You know, for $60,000, I can put up with a lot of bad management like these controllers were complaining about!’”

He applied and did well on the aptitude test. Then he traveled to Oklahoma City for a pass-fail screening. He passed and was sent to the Minneapolis Airport. “I stayed there my whole career, which is really unusual for controllers,” Dave said.

Mary left her daycare supervisor job, and, pregnant with their son Travis, moved to Minneapolis. Later, they had another son named Tyler and a daughter, Rachael.

Although Dave took all his children flying, only Travis showed an interest. He was working on his pilot’s license when he also got hired by the FAA as an air traffic controller. He worked in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and then was hired at the Minneapolis Airport. He did not complete his pilot’s license, however.

Dave, now retired, said that Travis, “has a better knack for it than I did. I mean, every controller likes to think they’re the best, but I think Travis is at least as good as I was, and he’s calmer about it. So, he didn’t have quite as big an ego as I did.”

My First Experience with Flight

I am more into water than air. My hero was not Charles Lindbergh, but Jacques Cousteau, the undersea explorer I watched every Sunday afternoon on television. I swam competitively and I still canoe, sail, kayak, paddleboard–anything that will put me in or on water. I feel most at home in the tug and buoyancy of the lake or the sea–most like my true self.

In high school, when I had to select a poem to memorize, I chose “Sea Fever” by John Masefield, with lines like, “I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky/All I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by.” Dave would have chosen a poem like “High Flight,” with lines like “I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth.”

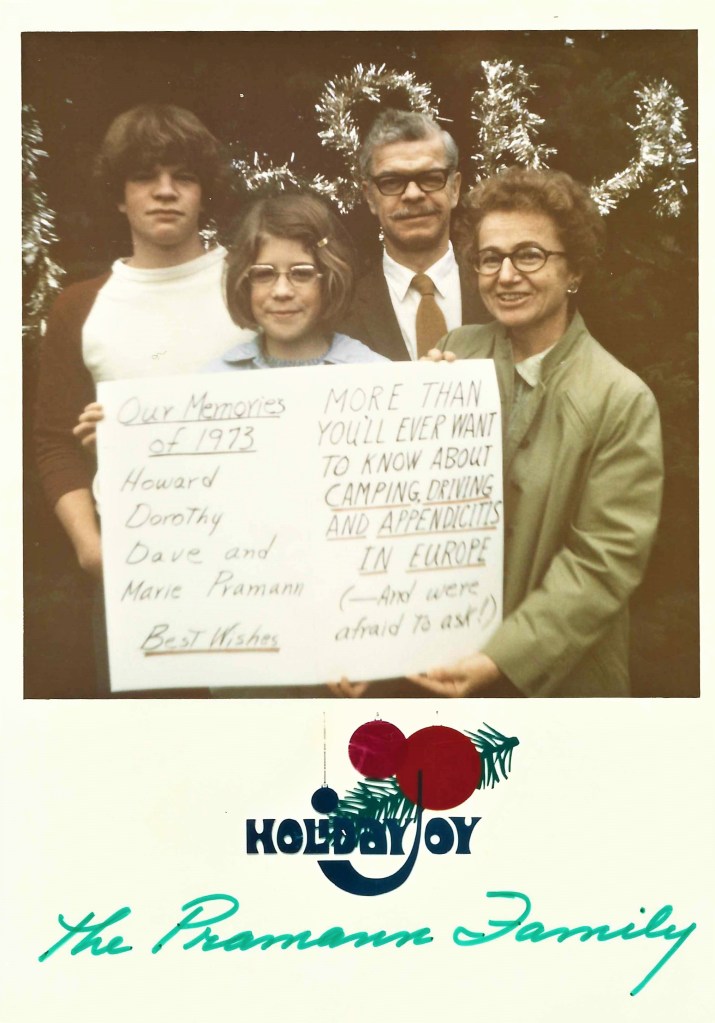

Like my brother Dave, my first flight was a bad experience. It occurred after fourth grade in 1973. My parents took Dave and me on a trip overseas to the U.K. and Europe. Our first leg of the journey was a flight from Duluth to Detroit. I recall not enjoying that first landing because it hurt my ears. As an adult, I was diagnosed with eustachian tube dysfunction. My ear tubes are very small, so it’s hard for me to equalize air pressure in them, especially on landings. Later, I found this to be true while scuba diving, too.

We landed in Detroit and had a layover before we left on the same plane to London. On our London flight, I was in a row with three seats. I sat next to the window, my mother was next to me, and then an elderly man who boarded in Detroit sat next to my mother. Dave and my father were seated elsewhere.

The flight across the Atlantic was uneventful. I recall being mesmerized by “cloud castles,” stacked cumulus clouds I could see out the window, formed from storms below. It felt like seeing heaven for the first time.

Once we got to London, we circled around Heathrow Airport for two hours before we could land. It could have been because of stormy weather or high air traffic volumes. If only we had landed right away, maybe my story would have been more pleasant.

As it was, the circling began to make me nauseous. Then the man seated by my mother started feeling ill, too. His face literally turned green, which I had never seen happen to anyone before. He began moaning and threw up into the airsickness bag.

My mother, alarmed by his condition, got out of her chair to seek help, leaving me alone with the sick man. That was more than I could handle. I plugged my ears and closed my eyes to escape the scene, like one of the proverbial three wise monkeys.

After what seemed an eternity, my mother returned with a doctor in tow. While the man was being attended, I kept my ears plugged and eyes closed. I don’t recall my mother returning to her seat. Maybe she stayed away to allow the doctor room to work. As the plane continued circling, my queasiness increased. I did not throw up, but by the end, wished that I would so I could feel better.

When we descended, my ears acted up again, adding pain to my nausea. Upon landing, I was extremely happy to see the ground. My moaning seatmate was carted off first. Freed from his proximity and on solid earth once more, I began to feel better.

My mother later learned that the man had a heart attack on the plane. He survived but did not have the European vacation he expected. He returned home directly after being released from the hospital.

We picked up our rented Dormobile (rather like a Volkswagen campervan) and drove to the campground where we had planned to stay for a few days while we explored the sights of London.

A few months before our trip, I had begun having some intestinal issues, which acted up while we were camping, perhaps from the stress of the flight. I don’t recall much except lots of bathroom visits (and being impressed that the toilet tank was hung on the wall far above the toilet).

After two nights, I was throwing up green bile and was barely conscious. I told my parents I thought I was dying. They called a doctor, who called for an ambulance. I was whisked away to Sydenham Children’s Hospital.

I passed out in the ambulance. When I awoke in the hospital, I threw up. I remember my mom sitting outside the exam room, crying. I don’t remember anything else until I woke up after surgery, feeling much better. They had taken out my appendix and explored around the rest of my intestines, which made for a larger scar than usual. The doctor said my appendix probably didn’t need to be removed, but that my intestines were inflamed.

The pain was gone–that’s all I knew. I spent the next two weeks in the hospital, which wreaked havoc on my parent’s travel itinerary. But they had planned to travel for six weeks so our trip was able to get back on track once I recovered.

At our last campsite, my excitement to return to the familiarity of home overruled any worry I had about reboarding an airplane. Those flights all went well–no heart attacks, no endless circling, no appendicitis. Unlike Dave after his first flight, I had little desire to pursue an aviation career or to ever fly again! But I did my fair share of air travel later, mainly for work and pleasure trips.

Conclusion and Acknowledgements

This story was inspired by a trip I took to Chicago in the fall of 2023. True to my watery nature, I have spent most of my career working as a writer for a water research organization called Sea Grant. Every few years, the Sea Grant programs gather for a Great Lakes Sea Grant Network Conference where we share information and collaborate with each other.

The four-day event is capped by an evening awards banquet where outstanding staff and projects are recognized. During the banquet, I happened to sit next to John Brawley, a staff member for Lake Champlain Sea Grant, which has an office in Burlington, Vermont. I’d been to Burlington for a previous Great Lakes Sea Grant Network Conference and knew that Camel’s Hump is visible from town. During casual conversation, I mentioned to John that I had an uncle who died in a plane crash on Camel’s Hump.

This seemed to spark his interest, so I went into greater depth. As I talked, John’s gaze became more intent. Finally, he broke in saying, “I can’t believe it! My girlfriend and I climbed Camel’s Hump and saw that plane just last year.” He then showed me his cell phone photos of the plane’s wing surrounded by underbrush. He was flabbergasted to learn that I was related to the pilot in the crash. His attention made me feel almost like a celebrity. When I returned home and relayed the conversation to my relatives, I realized the crash story is pretty interesting. I’d always taken it for granted, and not every family has such a one to tell.

So, I decided to research the history of flight in my family. Speaking with my relatives and Brian Lindner, I came to understand better events from my childhood. Reading my Uncle David’s letters (provided by Lindner) brought him alive for me. I felt like I knew him better than many of my living relatives – only to lose him again as I read accounts of the crash.

Uncle David was buried in a sealed casket in the Springfield Cemetery where the wind carries the melodies of meadowlarks and wailing train whistles.

“Son of Lassie” was released in 1945, a year after David’s tragic death. I wonder if his parents and siblings watched it then. If so, did it offer comfort or dredge up more grief?

Inez ended up marrying Robert Collison, a Canadian logger. My mother kept in touch with her and my family traveled to Canada to visit her and Robert in Clearwater Station when I was three. I had no idea then that she was the former girlfriend or fiancée of my Uncle David. I just thought Inez and Robert were friends of my parents.

The Camel’s Hump incident became known as “Vermont’s most famous plane crash.” Every one of the men on that plane was eager to serve his country and had so much to give. We’ll never know what contributions they would have made. A plaque at the base of Camel’s Hump commemorates the crash and those who died in it.

I did not have as much information about my Uncle Dick. Because he lived on the other side of the United States from us, visits were few. I only recall seeing him a couple of times but have incorporated my impressions into this story along with those from others.

And, of course, the information provided by Brian Lindner was invaluable. We talked on the phone twice and he sent me copies of David’s photos, letters, and crew orders. I also interviewed my cousin Ginger Beske and brother Dave Pramann, along with internet research. Dave also found the weather information for the time period surrounding the Camel’s Hump crash.

My dearly departed mother, Dorothy (Potter) Pramann, provided her memories of growing up in Springfield through notes for a speech she gave at her high school class fiftieth reunion. She also had the foresight to save many newspaper articles about relatives and distributed copies to us.

I also appreciate the help of my writing group members, Linda Olson and Lacey Louwagie, for their keen editorial eyes. Although I use storytelling techniques in this work, all information is backed by facts or people’s recollections, and sometimes both things.

Grief settled over me for days while I wrote this, but I feel like it’s a necessary emotion and one that comes with the territory when working on such a story. If Uncle David were a ghost reading over my shoulder as I wrote, I like to think he’d be happy knowing that the love of flight lives on in at least one branch of our family– from the cornfields of Springfield, to a remote mountaintop in Vermont, and the runways of the Minneapolis Airport.